The way is shut. It was made by those who are Dead, and the Dead keep it, until the time comes. The way is shut.

J.R.R Tolkien

Into the dark they crept, with fire in hand and water underfoot. Deep in the dark they offered all they had left — the last of their precious corn, their spilled blood, their innocent children.

But it was no use. The gods did not listen. The rains did not come. And there, in the dark, they watched their world end.

On the morning of May 4th, I woke up to the dawn chorus of birdsong and the sweet smell of hot, jungle humidity. It was the fifth day of our honeymoon in Belize and we had already seen and done so much. What had begun as an adventure in the heart of the rainforest at Black Rock Lodge had now transformed into an exploration of Maya culture and history.

We had stopped at the hilltop ruins of Xunantunich the day before, and with Table Rock Jungle Lodge as our new base, we were looking forward to a couple tours of famous Maya sites with Belize Nature Travel.

First on the list was Actun Tunichil Muknal, the cave of the stone sepulchre — better known as “the cave of the crystal maiden.”

Discovered in 1989, the “ATM” cave lies hidden in the Belizean jungle, partially submerged in an underground river. To the ancient Maya, it was known as Xibalba, the Underworld, and for good reason. Once inside, three miles of twisting passageways lead to pitch-black caverns and the scattered, crystallised remains of 14 Maya people — all sacrificed at the height of the collapse of the Central Lowland civilisations in the Classic Period.

It is the only place in the world where you can physically walk through the last days of the Maya world. Starting in the entrance of the main cavern, you’ll follow evidence of their growing desperation from 750 to 850 AD and finally, 950 AD at the dead-end of the cavern. It is also the first place in history to reveal real, concrete evidence of human sacrifice in Maya culture.

We knew that exploring such a sacred, fascinating place would be a true privilege and an adventure of a lifetime — but first, we had to get there.

The journey to the cave would take us on a rocky road from San Ignacio into the beautiful Tapir Mountain Nature Reserve, crossing the Roaring River three times during a sweaty jungle hike.

The road to Hell

At breakfast that morning we met John and Suzy, a friendly middle-aged couple from Arizona who would be joining us on our tour with Belize Nature Travel. Together, we made a small group of four which was brilliant.

Our guide picked us up at 7:30am, and we all climbed into his big silver van. His name was Patrick — Patrick Bradley — which happened to be the same name as Patrick of course, as well as Suzy and John’s two sons Patrick and Bradley! We all figured that the strange coincidence meant good luck for our tour. To avoid confusion, I’ve referred to him as “our guide” from here on out.

The drive to the cave took about an hour, and there was plenty to see and talk about along the way. Our guide told us all about Kriol, Maya and Mestizo culture, as well as about the Mennonite and Chinese communities who have made Belize their home in recent decades.

We passed through tiny Maya villages with funny names like “Blackman Eddy” and “Teakettle”. Although their names sounded colonialist, we learned that most were named after events or landmarks. A black man was found drowned in an eddy, and Teakettle sits right along a river basin that forms the shape of a Teakettle, for example.

Our guide also told us that he was half Kriol (the Belizean spelling for creole), a descendent of a British settler and an African slave, and he spoke Kriol, a mix of simplified English and African dialects that can be heard throughout Belize. As Belize used to be British Honduras, a British colony, English is the official language but most Belizeans learn and speak Kriol to one another in daily life.

When a couple loose horses ran out into the road (which no one on the road seemed too concerned about) he shouted “hasses, hasses!” at the cop we passed by (who also looked too laid-back to care).

On the banks of the Styx

When we reached the cave parking lot, I was surprised to see that we were the first group to arrive — all was empty and quiet. Anxious to get to the cave before the larger tour groups pulled in, we quickly changed into our water shoes and left anything of value in the van. All we needed for the cave was the swimsuits and water shoes we had on, plus a pair of socks to wear in the sacred part of the cave. Our guide provided our helmets and headlamps, as well as a packed lunch.

Cameras and phones have been banned for a few years now after one stupid tourist dropped his camera on one of the ancient skulls. I can’t imagine the complete and utter shame and embarrassment they must have felt, but how on earth do you make that mistake!?

Since I didn’t have my camera or phone, I missed out on some great shots from the jungle hike and cave tour, but it did make me live in the moment, which I appreciated for such an incredible experience. All of the photos you see in this post were provided by Belize Nature Travel.

Heading down the path, it wasn’t long before we saw the Roaring River. It resembled a lagoon more than a river, and it definitely wasn’t roaring. Its clear and green waist-deep water remained perfectly still as we crept in and swam across. Once again, I had to calm my intense fear of crocodiles, but we reached the other side safe and sound.

From there, we entered a jungle with some of the largest palm trees we had seen yet. The 45-minute walk was flat and easy which we were thankful for in our thin water shoes. We crossed the Roaring River twice more, but by this point the glassy water only reached up to our ankles. I remember kicking up hundreds of beautiful coloured rocks as if that mystical river was full of gemstones. The view from the middle of the river was also stunning, with lush green jungle hills jutting out from either side.

Entrance to the Underworld

After a while, the jungle seemed to grow thicker and more wild. Our path became a bit rockier, until it ended without warning.

There before us, partially submerged in the shallow river bed, was the entrance to the Actun Tunichil Muknal cave. The river water, still clear as glass, had deepened into a dark turquoise and cascading vines covered the limestone walls. It was a scene right out of the Lost City of Z or Apocalypto. Carefully, we made our way down the slippery rocks and waded into the cool water.

Swimming into the cave was surreal. The last of the light from the outside world danced off the water and bounced off the walls, just bright enough to reveal the bats swooping overhead and the small, pale fish around me. The entrance hall was a great big dome, and I felt like I had wandered into tropical snow globe.

As we were the first group to arrive that morning, we had the cave to ourselves for most of the trek in. We turned our headlamps on and climbed up a limestone ledge. The narrow passageway lay ahead and I felt goosebumps creep up my neck as I stared into the darkness.

It was a feeling that must have been shared by the ancient Maya. They had called this cave Xibalba, the Underworld, or more literally, the “Place of Fright.” They believed it was home to three of the nine levels of Hell, and the demonic spirits of Hell, the Lords of Xibalba, guarded it well. Only the elite class, including kings and shamans, and nobles like astronomers and oracles, were allowed to enter.

It was a sacred place, a place of worship, where both a vital water source and the gifts of the gods could be found. They even saw the faces and profiles of their gods in many of the strange limestone formations. It felt a little eerie to pass by the long profile of the god of maize and the bowed head of the goddess Ix Chel with her snake-like tendrils. Not for the first time, I felt that we were trespassing.

Deeper and deeper into the cave we went, climbing over slippery boulders, squeezing through tight crevices and avoiding sharp rocks. Through it all, we were either walking through or outright swimming in the shallow water. I was surprised to find that I wasn’t shivering. The water was cold and refreshing but the air remained warm and humid throughout the cave.

I was also too focused on following the group to think about how dark it was or how far down within the earth we were, but there were times when I scared myself by looking a little too long into one of the smaller, pitch-black caverns. Something was surely in there, I thought, whispering riddles in the dark.

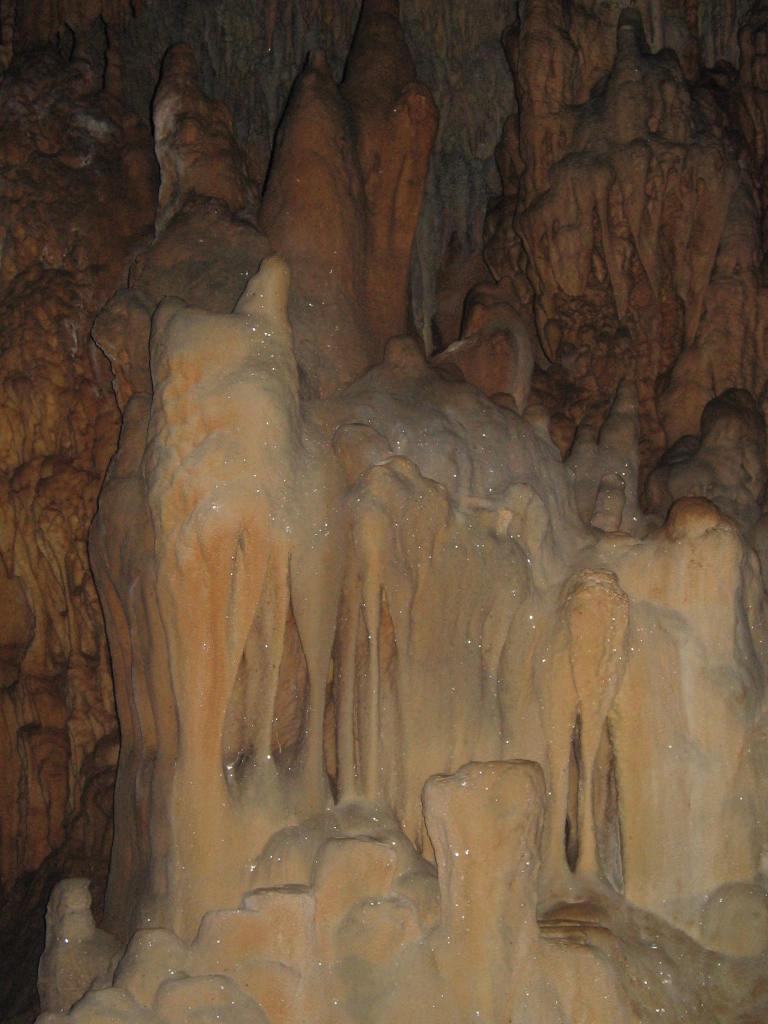

Each time we stopped, our guide asked us to turn off our headlamps. I’ve been in caves before, but experiencing complete and total darkness while treading water in an underground river was incredible. All we could hear for one long moment was the steady drip of water echoing in the distance. When our guide turned his headlamp back on, shadows leapt from the stalagmites and stalactites, desperately reaching for us with gnarled limps.

The most stunning sight, however, was the crystal “chandeliers.” They seemed to drape down from the cave ceiling like shimmering veils. They were diamonds in the rough and a welcome sight in the dark.

But they weren’t the only eye-catching shapes in the dark. In one cavern, our guide used his lamp to point out a large black slate stone with teeth-like ridges next to a sharp wooden slab. Sitting high up on a ledge above, their shadows grew long in the light. “Now it’s time to tell you the Maya Creation story”, he said.

It was believed that the first humans were moulded from clay but they were disobedient and had to destroyed. Never one to give up, the Creator tried again, this time carving humans out of wood but they too had to be destroyed (with the few survivors turning into monkeys and apes). Then the god of maize cut open his hand with a sharp blade and mixed his blood with corn. Humans sprung up from the mixture, and they were good and obedient.

Once we learned that the Maya believed that they were descended from this 3rd generation of humanity, the shadows cast by the black slate stone and pointed wood came to life — corn and a sharp knife. Maize and blood. The source of life.

We then learned that unlike other ancient peoples, the Maya didn’t leave petroglyphs or paintings on cave walls. Instead, they created moving pictures by shaping limestone or incorporating natural formations to cast shadow figures with their torches.

On sacred ground

Next, we arrived at the base of the Cathedral cavern, the sacred part of the cave. To get to it, we had to scramble up a particular slippery boulder to reach the top level of the cave. Back in the time off the ancient Maya, the river would have been much higher and they would’ve walked on the top-level ledges that now seemed so impossibly high up.

I was sure I would slip, but somehow I made it up to the top. The Cathedral cavern was aptly named. It was massive, new world of giant stalagmites — an underworld fit for the gods.

We took our shoes off and put on our socks to protect the ancient relics within and the natural beauty of the cave. Our guide showed us how to walk on the limestone ridges. Pottery — and even bones — might be resting in the small crevices between them, he said.

Almost immediately we came upon the clay pots. Some were shattered and thrown about while others remained mysteriously intact. There were hundreds, if not thousands of pieces scattered all around the Cathedral cavern. Why were they left here? Had they been broken on purpose?

Our guide told us that the Maya began to leave offerings of corn and beans in these pots in 750 AD. By this point in time, extreme drought had arrived and they were suffering greatly. In effort to build larger cities and taller pyramids, they had decimated the rainforest and caused massive deforestation, which in turn had brought about dustbowl-era conditions.

They had hoped that leaving their best food in the clay pots would be enough to earn the gods’ mercy, and they shattered each pot to ensure the food would make it into the spirit world. Sadly, the drought only worsened and they were running out of options.

And so, the blood-letting began.

As we walked deeper in to the Cathedral cavern, our guide pointed out intact black pots left beneath the blackened, soot-covered cave ceiling. By 850 AD, royals and shamans, under extreme pressure to deliver upon their promises of salvation, began to offer their own blood to the gods. Using a sting ray barb and the aid of hallucinogenics, the women pieced their tongues and nipples, and the men pierced their penises. They then burnt the bloody paper in a pot, and hoped the smoke would carry it to the gods.

Yet, it still wasn’t enough. By 950 AD, their way of life was rapidly collapsing and their desperation turned into madness. They put all their hope in the pure blood of innocents.

Walking farther into the cavern, we began to see several bones scattered amid the pottery — a finger bone embedded in the limestone and a femur covered in calcium deposits. Then we saw fragments of an infant skull in a small secluded crevice. As a symbol of purity, many babies were left to die in this dark, terrifying place.

For some reason, the terrible reality of sacrifice didn’t hit me until we saw the skull of an elite teen. With his unnaturally long skull and flattened forehead (head shaping was common among the elite Maya), he looked more alien than human. Yet, he had suffered a very human death, as seen in the gaping hole in his head.

Whether he went to his doom willingly or not, I thought of the fear he must have felt before the final blow from a sharp rock ended his short life.

In the tomb of the crystal maiden

To reach the final cavern, we had to climb up a rickety old ladder to another level of the cave. This cavern was exceptionally small and narrow, and felt more like a tomb than the other caverns. We had reached the dead-end of the cave, and the end of days for the ancient Maya of Belize.

We soon came upon the remains of another teen — this one was a commoner and perhaps a captured slave or prisoner of war. Their skull had not been shaped or flattened, and the features that stared back at us were all too familiar. Whoever they were, it was clear that their hands had been tied behind their back and the hole in their skull again revealed the brutal wound that had killed them.

Then, just ahead, we saw her. Covered in centuries of glittering calcified rock, she was more fossil than bone. Her name suited her well — the Crystal Maiden. She lay spread out on her back, as if she had simply fallen asleep, but her face was ghoulish and twisted into a silent scream. I thought she must have been killed in a terrible way, bound and beaten like the other teen, but our guide said that she had actually been a volunteer. She would have lied down willingly, and her arms and legs would have been cut open to allow her to bleed to death peacefully.

For over a thousand years, she has lain here in this dark, cold place. It was a chilling thought to think of her last thoughts, knowing that she would never leave the cave again.

Back into the light

Down the ladder and over the the slippery boulder we went, crashing down into the river and creeping through new, even narrower passageways. As we made our way back into the jungle and into the light, the howler monkeys began to roar and the birds began to sing. We had returned to the land of the living.

We really felt that we had travelled to Hell and back. Each cavern had revealed more death and more to the story of the Maya in their final days.

We learned that not long after the Crystal Maiden had met her fate, the Maya abandoned the ATM cave area, heading for the deeper jungles of modern-day Guatamala. By the time the Spanish arrived in this part of Belize, the Maya were already long gone. Perhaps that in itself was a bit of mercy, considering the war and disease that followed the Spanish conquest. Perhaps their gods has listened after all.

Exploring the ATM Cave was a surreal, and once-in-a-lifetime adventure. More than that though, it was a privilege to enter such a sacred place and to walk the same dark passageways as the ancient Maya. The fear they must have felt as their world fell apart, their determination to survive and the reverence they showed within the cave has left a real mark on the place. You can feel the spiritual power with every step you take.

It is an incredible, beautiful place that must be respected — after all, it is the entrance to Hell.

3 responses to “Paths of the dead in the ATM cave of Belize”

[…] and river cruising, exploring the Maya ruins of Xunantunich, Caracol and the dark underworld of Actun Tunichil Muknal. Next, we would begin our road trip to the coast and the pristine beaches of […]

LikeLike

[…] from birdwatching, most of our time at Table Rock was spent exploring the nearby Maya sites of Actun Tunichil Muknal and Caracol. But whenever we had the chance, we swam in the gorgeous saltwater pool and relaxed […]

LikeLike

[…] had explored the mysterious Maya ruins of Xunantunich, the dark passageways of the Actun Tunichl Mucknal and the wild forests of […]

LikeLike